Whether used for work, sports, recreation or companionship, horses need high-quality forage. Not all hay has the same quality, even that grown or harvested at the same time. Quality hay has a high nutrient content and is free of dust, mold, and other foreign matter. Horses can be nutritionally deficient even when plenty of forage is avail- able to them. Alternately, leisure horses can be overfed and encounter health problems due to diets too rich from very high-quality hay. Knowing the hay’s forage quality is the key.

This publication describes the nutrient needs of horses, helps you determine how much and what quality hay you’ll need, and provides a detailed checklist to guide you when contacting hay sellers.

Horses are natural forage eaters. Though not ruminants, they do best with forage-based diets. A horse’s front teeth are ideally adapted for biting off grass. Its back molar teeth are better adapted for chewing feed such as pasture or hay than for grinding corn. Horses have a smaller digestive tract than most ruminants and cannot handle as much bulk at one time. Even so, lack of sufficient forage in a horses diet can lead to digestive orders.

The myths of feeding horses

There are more myths associated with feeding horses than with most other animals. The myths are often spread by horse owners who have little basic animal nutrition training. For some, “horse hay” means dry, dust-free, mature grass hay. This type of hay tends to be low in energy and protein, and may not meet the horse’s needs. Grass hay or grass mixed with mature legumes is often best for mature idle horses that are housed primarily indoors. However, young growing horses, pregnant or nursing broodmares, and athletic performance horses need more energy, protein, vitamins and minerals than this type of hay can provide. Some horse owners erroneously believe that feeding high-quality hay that contains legumes invariably leads to digestive upset. In fact, high-quality hay (e.g., young alfalfa) can reduce the need for additional supplement and will not cause digestive problems unless the quality or amount fed exceeds the animal’s needs.

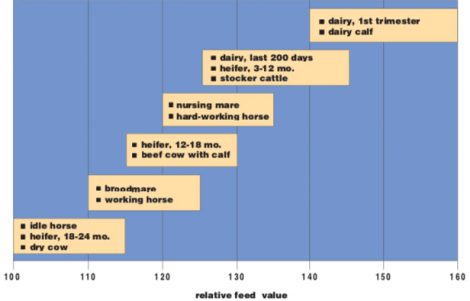

A more responsible approach is to recognize that all horses need some hay and pasture. Feeding costs gener- ally decline and animal health improves as hay is maximized and grain is minimized in the horse diet. This can be accomplished by feeding the highest quality forage appropriate for your horse. The best quality forage for your horse will depend on many factors including age (growing vs. mature), physiological stage (e.g., pregnant vs. not), and activity level. Refer to figure 1 for specific forage quality needs for different activity levels.

The horse’s digestive system

The horse’s digestive system is vastly different from other large domestic animals (ruminants). While horses are natural forage eaters, they do not have the large rumen for forage to flow into and be digested by microbes. Instead, consumed feed goes immediately to the stomach, which has relatively limited capacity. This is why horses are more susceptible to molds that would be digested in the rumens of cows or sheep. Feed passes more rapidly through a horse’s digestive system than it does through a ruminant’s, preventing them from using low-quality hay as effectively. This difference in digestive physiology also means that horses should be fed more frequently rather than given large amounts in a single feeding.

The horse’s digestive system is vastly different from other large domestic animals (ruminants). While horses are natural forage eaters, they do not have the large rumen for forage to flow into and be digested by microbes. Instead, consumed feed goes immediately to the stomach, which has relatively limited capacity. This is why horses are more susceptible to molds that would be digested in the rumens of cows or sheep. Feed passes more rapidly through a horse’s digestive system than it does through a ruminant’s, preventing them from using low-quality hay as effectively. This difference in digestive physiology also means that horses should be fed more frequently rather than given large amounts in a single feeding.

Once the horse takes a bite of the hay or pasture digestion begins as the forage is chewed and wetted with saliva. A horse will normally add 3 gallons of saliva to the feed daily. Chewing reduces the particle size of the forage and increases its surface area. Forage enters the stomach where soluble carbohydrates, proteins, fats and some minerals are enzymatically digested as would occur in our stomach. In about 15 minutes the forage goes into the small intestine where a high percentage of the protein, starch and fats from grain diets is digested to amino acids and absorbed. Only about one-third of the roughage component is digested in the small intestine. Most of the vitamins A, D, E, and K are absorbed in the small intestine along with calcium, phosphorous, and B vitamins. Forage remains in the small intestine for 30–90 minutes.

The cecum and large colon of the horse is enlarged compared to ruminant species. This section of the horse’s gut serves a function similar to the rumen and contains many species of bacteria, protozoa, and fungi to digest the fibrous components of feed (cellulose and hemicellulose). The microbes convert fiber and other feed components to volatile fatty acids which are absorbed by the horse as an energy source. These microbes also manufacture some protein, B vitamins, and vitamin K. The feed then proceeds through the small colon and rectum. Approximately 65 hours after it was consumed, the digested feed leaves the animal.

Nutrient needs of horses

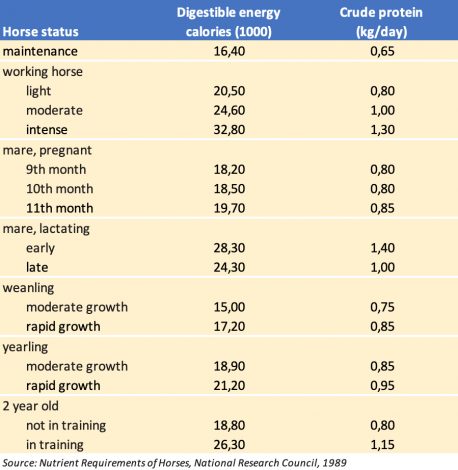

The nutrients a horse needs depends on its physiological stage and activity level. Table 1 outlines the protein and energy requirements for various horse types. In general, a young growing horse has the highest requirement for energy, protein, minerals and vitamins per pound of body weight. This means that its diet needs to be the most concentrated in nutrients. In contrast, a non-pregnant, mature horse that is ridden less than daily (mature idle) has the lowest nutrient requirement. Other classes of horses fall in between these extremes. Horses that are worked hard daily or exposed to cold winter temperatures have slightly higher energy needs than idle horses.

So how do you decide what quality of forage to buy? You’ll need to calculate the percent crude protein required and you’ll need to consult figure 1 for the appropriate relative feed value. A mature, idle horse that weighs about 500 kg requires a minimum of 0,65 kg of crude protein per day (from table 1). If the horse eats 2% of its body weight per day, it’s consuming 22 pounds of hay. To determine the percent of crude protein needed, divide the crude protein requirement (0,65 kg/day) by the hay consumed (10 kg/day) and multiply by 100. In this example, hay that has at least 6.5% crude protein will provide all of the protein the horse needs; no additional protein supplements are needed. Based on this information, hay with a relative feed value (RFV) of 100–115 and crude protein (CP) of 6.5–15% will be adequate for this animal.

Selecting quality hay

Depending upon the use or the classi- fication of the horse (maintenance, pregnant, lactating, etc.), hay can supply 50–100% of the needed nutri- ents. When buying horse hay, you should select the quality your horse needs at the lowest cost. To determine the quality needed, refer to figure 1 below.

Forage quality encompasses all charac- teristics that affect consumption, nutrient value, and resulting horse health and performance. Not surpris- ingly, there can be wide variations in hay quality. Hay can be analyzed to estimate how the horse will perform. But ultimately, it is the horse rather than the human that determines forage quality.

Quality terms

The following terms are commonly used to measure hay quality. When evaluating values, be sure they are expressed as a percent of dry matter of the hay. The numbers following each definition (where appropriate) represent the ideal range for horses.

Dry matter (DM). The percent of the forage that is not water.

Acid detergent fiber (ADF). The percentage of highly indigestible and slowly digestible material in the forage or feed. Lower ADF indicates more digestible forage and is more desirable. (30–45% dry matter)

Neutral detergent fiber (NDF). The percentage of cell wall material or fiber in the feed. Lower NDF results in greater animal consump- tion. (40–50% dry matter)

Crude protein (CP). A mixture of true protein and nonprotein nitrogen. Crude protein percentage indicates the capacity of the feed to meet an animal’s protein needs. Forage cut in early maturity or with a high leaf-to-stem ratio has a high CP content. (8–20% dry matter)

Digestibility. The percentage of the forage that would be digested in a rumen. May be measured by in vitrodigestibility (more accurate) or cal- culated from ADF (less accurate). Though horses do not have a rumen, this is the best estimate of energy available to them from a forage. Digestible energy is the energy in a forage that is processed by an animal and not excreted in feces. (50–60% dry matter)

Relative feed value (RFV). A cal- culated index used to rank forages by potential intake of digestible dry matter. Average full bloom alfalfa hay has an RFV of 100. Higher- quality hay would have an RFV greater than 100. Protein is not used in calculating RFV. (100–135)

Total digestible nutrients (TDN). The sum of crude protein, fat (multiplied by 2.25), non-struc- tural carbohydrates, and digestible NDF. TDN is often estimated by cal- culation from ADF. It is better esti- mated from in vitro digestibility.

Quality differences and determination

Quality differences exist among grasses and legumes, plant species, growth stages, and growing environment. Legume hay and well-managed legume-grass hay are typically higher in protein, energy, and minerals than pure grass hay under similar management. However, with good management, most hay species or mixtures can be satisfactory for horses.

The most important factor affecting quality is the stage of maturity of the forage when it is harvested. As forage plants mature (from the vegetative stage to flower bud to bloom to seed formation), their nutritive value declines because they have fewer leaves and more stems (lower protein, higher fiber). For high-quality hay, alfalfa should be at the 10% bloom stage and cool-season grasses (orchardgrass, bromegrass, timothy, etc.) should be at the boot stage (seed head just ready to emerge from leaf whorl). Subsequent harvests can be taken at 30- to 35-day intervals.

Hay quality is determined by analysis of a sample at a forage testing laboratory. A hay analysis typically includes percent moisture, dry matter, acid detergent fiber, neutral detergent fiber, crude protein, and mineral content with many calculated values such as net energy, total digestible nutrients (TDN), and relative feed value (RFV).

Laboratories can analyze hay either by chemical or near infrared reflectance (NIRS) methods. Both are accurate. Allow 2 weeks for chemical analysis and 2–3 days for NIRS analysis.

Taking a representative sample

Taking a representative sample

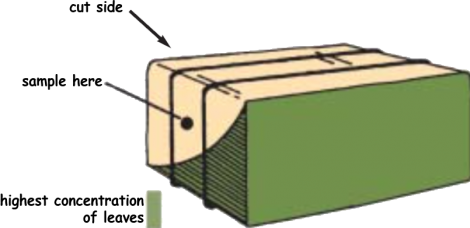

Taking a representative sample for hay analysis is essential. The labo- ratory will accurately analyze the sample, but if the sample does not represent the hay lot, the analysis will be meaningless. A few grab samples from hay flakes do not represent a cross-section of the bale and should not be used! The preferred sampling tool is a bale probe (14–24 inches long with a 1⁄2-inch diameter) designed to attach to an electric drill or brace. Using the probe, take a core from the center of the end of 20 different small square bales (see figure 2). Combine the cores thoroughly and submit a 1⁄2-pound sample. Medium-sized bales (800–1200 lb) can be sampled anywhere on the ends. Round bales should be cored on the curved side straight in towards the bale center. If grab samples must be taken, be careful that the samples taken have the same leafiness as the rest of the bale. As with core samples, take several grab samples (because bales vary) and combine them to produce a single sample for analysis.

Visual criteria for quality

Visual criteria for quality

In addition to laboratory analysis (for dry matter, energy, protein and minerals), a visual inspection should be made. Evaluate the hay for leafiness (steminess), fineness of stem, color, odor, and freedom from weeds, molds, or other contaminants that will reduce animal consumption and cause health problems.

Leafiness is closely related to nutritive value and quality. Leaves contain more nutrients than stems. Baling before plants mature, baling at the proper moisture content, and having minimal insect and disease problems will help retain leaves on the stem. Loose leaves in the bale can be lost during handling and feeding.

Color is often deceiving and overestimated as an indicator of quality. Although bright green hay often indicates the absence of rain damage, weathering, molds, and heat damage, be careful not to evaluate bales on color alone. Color can be misleading for a variety of reasons. For example, bales are commonly bleached on the outside while the inside is still very green. Bright green weeds may have lower nutrient value than bleached alfalfa. Leafy bleached hay may contain as much energy and protein as green hay if leafy. Hay preservatives (i.e., propionate) may reduce the bright green color of fresh hay, but they also reduce the leaf loss and improve digestibility of the forage.

Odor may be indicative of molds or bacterial growth that could cause digestive problems. Many horses that are unaccustomed to the unusual odor of preserved hay may initially reject it, but generally consume it readily after a few days of acclimatization.

Texture or softness relates to stem size and palatability. Fine- stemmed hay that is “soft” to the touch indicates to some extent palatability or acceptance by the horse. Brittle hay may or may not be nutritious, but if horses have trouble eating it they will not perform well.

Freedom from mold, injurious weeds and insects, dust, and foreign matter will reduce the potential for animal health problems. Refer to the list on pages 6 and 7 for a description of factors and symptoms to watch for.

Toxicity problems with hay

Contact your veterinarian immediately if you suspect your horse has ingested or inhaled a poisonous substance.

Fungi

Dust and molds: Moldy and dusty hay can cause health problems affecting the horse’s respiratory and digestive systems. A musty odor indicates the hay was harvested too moist, allowing molds to develop. The severity of a mold problem depends on the feeding conditions (is the space well ventilated?), the horse’s ability to tolerate mold or dust, and the dust and mold itself. The best test of dust or mold is to smell the hay. A laboratory analysis for mold will not be helpful since many molds are not harmful.

Dust and molds: Moldy and dusty hay can cause health problems affecting the horse’s respiratory and digestive systems. A musty odor indicates the hay was harvested too moist, allowing molds to develop. The severity of a mold problem depends on the feeding conditions (is the space well ventilated?), the horse’s ability to tolerate mold or dust, and the dust and mold itself. The best test of dust or mold is to smell the hay. A laboratory analysis for mold will not be helpful since many molds are not harmful.

Ergot: This fungus produces large, dark, spur-like structures protruding from the seedheads of cool-season grasses (brome, fescue, orchard, ryegrass, timothy, bluegrass, and quackgrass) and small grains (barley, oats, wheat and rye). The occurrence of ergot varies year to year and is triggered by cool, wet conditions during the spring period. Ergot can cause gangrenous type of poisoning and abortion. Ergot can be prevented in hay by harvesting before seedheads appear.

Plants

Brackenfern: The first signs of brackenfern poison- ing in horses are usually an unsteady gait, a “tucked up” appearance of the flanks, nervousness, timidity, conges- tion of the visible mucous mem- branes, and constipation. Later, the horse may stand with legs spread.

Cocklebur: Seeds and seedlings are the most toxic due to present of glucosides. Symptoms include loss of appetite, staggering, spasmodic contraction of leg and neck muscles, paralysis anorexia, reduced responsiveness, vomiting, rapid weak pulse, and muscular weakness.

Foxtail millet: Foxtail millet has been reported to have a diuretic effect on horses. In addition, barbs from the coarse, fuzzy seed heads may become embedded in the horse’s mouth.

Hoary alyssum: Horses experience depression and a “stocking up” or swelling of the lower legs. A fever and short-term diarrhea may occur as well as a founder with a stiffness of joints.

Horsetail: Ingestion of foliage causes loss of condition, excitability, unthriftiness, staggering gait, rapid pulse, difficult breathing, diarrhea and emaciation. Death preceded by convulsions and coma.

Milkweed, common: Weakness, loss of muscle control, and staggering appear soon after ingestion. Seizures, rapid breathing, and dilated pupils also occur. The toxin is a resinoid— galitoxin—but the foliage also contains glucosides and alkaloids.Nightshade family (black nightshade, horse nettle, jimpson weed) Foliage and green fruit contains alkaloids affects the nervous system causing weakness, trembling, labored breathing, nausea, constipation or diarrhea, death. First symptoms may be paralysis of tongue and dilated pupils.Red clover, hay and pasture Red clover hay may trigger excessive salivation, which is more of a nuisance or cosmetic issue than a danger to the horse. Slobbering appears to be associated with a fungal plant disease called black patch.

Milkweed, common: Weakness, loss of muscle control, and staggering appear soon after ingestion. Seizures, rapid breathing, and dilated pupils also occur. The toxin is a resinoid— galitoxin—but the foliage also contains glucosides and alkaloids.Nightshade family (black nightshade, horse nettle, jimpson weed) Foliage and green fruit contains alkaloids affects the nervous system causing weakness, trembling, labored breathing, nausea, constipation or diarrhea, death. First symptoms may be paralysis of tongue and dilated pupils.Red clover, hay and pasture Red clover hay may trigger excessive salivation, which is more of a nuisance or cosmetic issue than a danger to the horse. Slobbering appears to be associated with a fungal plant disease called black patch.

Tree leaves: The leaves of several species of trees are toxic to horses. These include oak, red maple, locust, and black walnut.

White snakeroot: Leaves contain the aromatic oil tremetol, which causes congestive heart failure in horses. Animals may be reluctant to move, stand with legs wide apart, and may stumble if forced to walk. Profuse sweating may be evident especially between rear legs. Bloody urine and/or choking may also occur. The toxin can be passed through the milk to foals.

Insects and animals

Other

Nitrates, high levels in hay or pasture High levels of nitrates may cause death. Symptoms include increased salivation, labored breathing, uncoordination, weak pulse, muscle tremors, vomiting, diarrhea, and suffocation. A characteristic finding is the chocolate discoloration of the blood and blueness of membranes. Some weeds—pigweed, lambsquarter, and nightshade—naturally accumulate nitrates. Grasses heavily fertilized with nitrogen (including manure) or produced under drought conditions may have toxic levels of nitrate and should be tested prior to feeding. If in doubt, have hay tested at any forage testing laboratory.

Which cutting to buy?

Horse owners frequently ask what is the best cutting to buy. Hay from any cutting can be very high or very low in quality depending on maturity of forage when cut and how good the haymaking and storage conditions were. Hay buyers should not be overly concerned about which cutting, but should instead ask about the stage of maturity when the forage was baled and an analysis of hay quality.

Hay preservatives?

Organic acid hay preservatives (for example, buffered propionic acid) properly applied at the time of baling inhibit mold growth that occurs in hay baled above 18–20% moisture and eliminate pockets of mold growth in hay. Their use can also decrease field drying times and reduce leaf loss by allowing for baling at up to 25% moisture. Research indicates that hay treated with most chemical preservatives is safe to feed to horses as long as no dust or mold is present.

Purchasing, transporting, and storing hay

How much hay do I need?

Horses will eat 1.5–2.5% of their body weight every day in dry matter. Grass or hay can meet 50–100% of that requirement. So if an 1100-pound horse eats 2% of his body weight each day in hay for 6 months, the horse will eat approximately 4000 pounds (2 tons) of hay. You can figure out how much hay your horse will eat using the calculations below.

Before placing an order, you’ll need to make several adjustments to the calculations. First, deduct any pasture consumed by the horse. In the upper Midwest, pasture can meet the full needs of most horses for 5–7 months of the year. Then factor in the amount lost to spoilage and feeding waste. The amounts lost vary depending on bale type and storage and feeding decisions and are discussed in the next section.

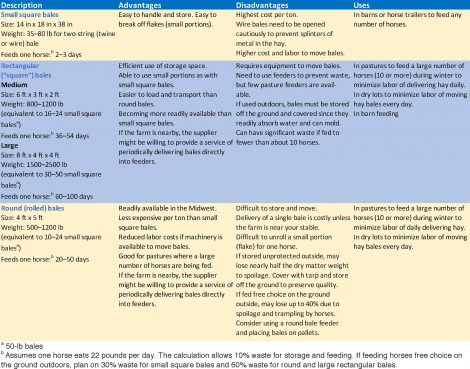

What kind of bale should I buy?

Traditionally, horse owners have preferred using small square bales. However, there are situations where owners should consider purchasing either large rectangular or round bales. If you will be remodeling your barn, it may be worth your time and money to consider accommodating large rectangular bales because these are becoming more available than small square bales and cost less per ton of feed. At a minimum, a 12-ft x 12-ft door is needed to back a truck in for easy unloading. For larger loads and trucks, consider a 16-foot-high door. For a comparison of the differ- ent bale types, refer to table 3.

No matter what type of bale you purchase, there will be differences in the weight of the bales. The type of hay, moisture content, and how densely the equipment packs or compresses it can cause substantial differences in the weight. Note that, especially with small square bales, you can get up to twice as much hay in some bales as in others.

How much hay will your horse eat in a year?

You can figure out how many bales or how many tons of hay your horse will eat in a year using the following equations:

Horse weight (kg) x (percent daily intake ÷ 100) = kg eaten/day

kg eaten/day x 365 days/year = kg/year

bales/year = kg/year ÷ kg/bale

tons/year = kg/year ÷ 1000 kg/ton

Example:

A horse weighs 500 kg and has a daily intake of 2%. Note the difference bale weight plays in the total number of bales needed when the average bale weight is 20 kg vs. 30 kg.

500 kg x (2% ÷ 100) = 10 kg hay/day

10 kg/day x 365 days/year = 3650 kg/year

bales/year: 3650 kg/year ÷ 20 kg/bale = 183 bales/year

3650 kg/year ÷ 30 kg/bale = 122 bales/year

tons/year: 3650 kg/year ÷ 1000 kg/ton = 3,65 tons/year